Alain Farhi (Spring 2005)

Major Sephardic Internet Site: Les Fleurs de l'Orient

by Alain Farhi

Avotaynu Volume XXI, Number 1, Spring 2005

The following is excerpted from a presentation given at the July 2004 genealogy conference in Jerusalem-Ed.

Les Fleurs de l'Orient (The Flowers of the East) is the name of a website that includes a major genealogical project (perhaps the largest of its type), personal documents and publications, a bibliography, references and links to genealogical sites, a compilation of Franco-Egyptian words and expressions used by many French-speaking residents of Arab lands in the Middle East, a message board, and photographs and memorabilia about the families mentioned. The site may be found on the Farhi website at www.farhi.org.

The genealogical project started with the Farhi families but now covers the genealogy of the major Jewish families originally from the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. It has expanded to cover links to Sephardim, Ashkenazim and Karaite families with their own ancestry and descendants in their new countries of adoption. The geographical distribution of listed families covers the world from Argentina to New Zealand.

My documentation of the Farhi family began in 1979, when, after my father's death, I found a suitcase of documents that came with us to New York after our (second) exodus from Egypt, where I was born. Among the surviving items were four pages handwritten in Arabic by my grandfather. He had drawn a four-family tree of the Farhis as he knew them. In the Sephardic tradition, only the descendants of men were recorded; once married, the daughters were no longer named Farhi and were dropped.

The genealogy "bug" bit me, and by 1985 I had translated the names on the four trees into English and had drawn them on a Macintosh computer into a graphic tree using the Mac's First Draw program. I mailed these trees to every Farhi I could find, those whose names I found in telephone books from around the world wherever I visited, and others brought to me by a friend who also traveled.

Between 1988 and 1995, the four pages grew into 21 branches, and I sent approximately 200 copies of that tree to those who had participated in the information gathering. The 21 families derived primarily from Farhis who had lived in the Ottoman Empire (Bulgaria and Turkey), but who now were living in Brazil, Canada, France, Israel and the United States.

In 1995, Maurice Hazzan of Paris (since deceased) tracked me down. Hazzan had compiled a tree of about 8,000 people of the major Egyptian Jewish families to whom he was related. Because a maternal aunt was married to a Farhi, Hazzan had taken an interest in the Farhis as well. His tree, however, included the families of Farhi women and their spouses.

Hazzan showed me, from my 1984 copies of the Farhi tree and with the help of professional British genealogists Lydia Collins and Morris Bierbrier, how he was able to include the descendants of the Farhi women, their husbands and the husbands' ancestry. Hazzan, also a Mac user, suggested Reunion genealogy software, and I moved my 21 branches away from a purely graphical representation into a database. For several years, Hazzan and I cooperated on our research, and each kept a copy of the other's database. By 1998, the 21 branches, now including Farhi women and their descendants, had grown so much that printing and mailing the updated graphics became a challenging effort.

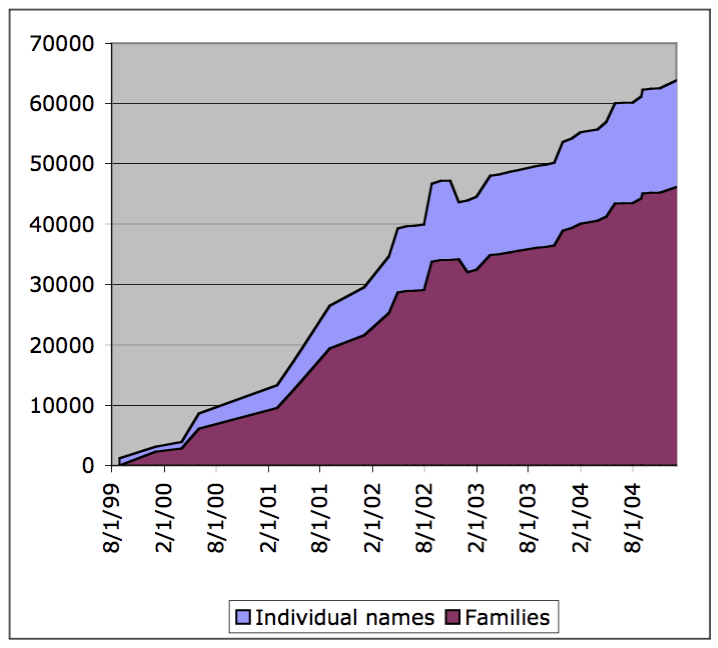

After visiting the Goldman Genealogy Center at Beth Hatefutsoth in 1999, where I learned how they disseminated the Farhi data that they had, I decided to publish my own tree on the Internet and to allow free access to my database of approximately 1,200 names. I registered the farhi.org domain name and launched my site. Instead of mailing reports, I directed queries to the website.

To gain visibility, I wrote to search engine operators requesting that they list my site. One was the soon-to-beborn Google (of whose existence I had learned when my son's college rooommate went to work for them). From early on Google indexed the contents of farhi.org. This early start gave Les Fleurs de l'Orient high ranking on the Google results page. This in turn brought in more genealogists seeking to add their data.

Maurice Hazzan died in 2000 before he could create his own website. In his memory and to preserve his work for others to share, I added his 8,000 names to Les Fleurs de l'Orient and linked them to the Farhi spouses. At this point, my genealogy effort was one big web of linked families. Both the ancestry and the descendancy of any family linked by marriage to a person already on the website was added.

As more people found relatives on the site, they volunteered to publish their own work, and the number of individuals listed on the site grew. Recently, I have stopped adding large new branches. Instead, I incorporate new data by creating a new tree on the same website. As of March 2005, more than 99,458 names were linked on Les Fleurs de l'Orient.

Unlike most commercial genealogy sites, museums (Beth Hatefutsoth) and the LDS (Mormon) church, where individuals post their own trees, all the trees and branches viewed on Les Fleurs de l'Orient are linked by marriage into a giant web of families. I update and correct the tree monthly to reflect the new data that flows in.

Naming the Site

The name Les Fleurs de l'Orient (translated from the French: Flowers of the East) is based on the origin of the Farhi name ![]() , which in Hebrew shares the same letters as the word flower (perah); l'Orient refers, of course, to the family's origins after their exodus from Spain following the Inquisition in the 16th century. In French, Les Fleurs de l'Orient also means "cream of the crop" of the Orient (families).

, which in Hebrew shares the same letters as the word flower (perah); l'Orient refers, of course, to the family's origins after their exodus from Spain following the Inquisition in the 16th century. In French, Les Fleurs de l'Orient also means "cream of the crop" of the Orient (families).

The original "Fleur" was Ishtori, son of Moses, son of Nathan. In his book, Kaftor va Perah (written late in 1340), he describes how he received his name. Ishtori was named after the town of Florenza, Spain, where his parents lived. In Spanish flora means flower (as perah does in Hebrew). Ishtori came to be know as haParhi, the surname later becoming simply Farhi.

Ishtori died in Palestine in 1357. We do not know if he ever married or had children. We do know, however, that he had two brothers, whom we assume remained in Spain and that their descendants left after the Expulsion in 1492. Some may have settled in North Africa, but the majority apparently went to the Ottoman Empire, where records exist of their having settled near Smyrna. From Smyrna they fanned out to all areas bordering the Mediterranean Sea-Algeria, Anatolia, Austria, Bulgaria, Egypt, Italy, Libya, Palestine, Romania, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen and Yugoslavia. Starting in the mid-19th century, the Farhis traveled to Central America, Europe, North America and South America.

My personal effort has been to trace all these descendants and, with their help, to trace their ancestral lines back in time as well.

From several sources, records of Farhi individuals unlinked to others have been found and compiled into three separate files. The files are:

Istanbul (marriage and death records, 18801890). This file contains the records of Farhi individuals who married or died in Istanbul, 1889-90.

Izmir (19th-century birth records). Included in this file are records of Farhi families who lived in Izmir (formerly Smyrna) during the

19th century.

Farhi Individuals from Other Sources. This file includes individuals found in Yad Vashem records, the 1920 and 1930 U.S. census records, U.K. census records and other documents found on the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture website (www.sephardicstudies.org/entrance.html). Records of Farhi individuals already shown on Fleurs de l'Orient are not duplicated here.

Karaites from the Crimea, Egypt and Russia. David Elishaa had compiled the genealogies of Karaite Jewry originally from the Crimea, Egypt and Russia, and now spread throughout the world. The tree includes 12,625 individuals and 8,663 families. The Karaite tree is linked to Les Fleurs de l'Orient through the marriage of Josette Massouda to Mark Farry (born Farhi) and Mirelle Lichaa to Pierre Ezri.

Weiner and King of Manchester, England. Many Sephardic Jews settled in Manchester in the mid-19th century to capitalize on the opportunities of the Industrial Revolution and its textile industries. Many of their descendants have intermarried with Ashkenazim. The tree of Goodenday, King, Musaphia, Salzedo and Weiner (and others) includes about 9,275 individuals and 6,511 families.

Peixotto and de Salzedo of Portugal and Holland. These families are linked to Les Fleurs de l'Orient through Annie Goodenday and David van Abraham Salzedo. They represent the Dutch and Manchester families that intermarried with Sephardim who had arrived from Aleppo and other parts of Syria. This tree has 5,498 individuals and 3,817 families. These Peixotto may be related to the Picciotto of the Ottoman Empire, but we do not have a link at present. The Ottoman Picciotto came from Italy, and the spelling of their name may be the Italian version of the original Portuguese Peixotto.

Nizard of France and Tunisia. The Nizard family is linked to Les Fleurs de l'Orient via their Tunisian descendants. The tree includes 383 individuals and 285 families. The French Nizards can be traced to the 17th century, but no link yet has been found to the 19thcentury Tunisian family.

Gubbay of Iraq. The tree of the Gubbays, originally from Iraq and the Ottoman Empire, connects to the Farhis through Ren≠e Farhi and consists of 730 individuals and 527 families.

Current Size and Distribution of the Database

As of February 2005, the website shows 98,611 individuals and 70,330 families. An additional 5,100 individuals representing 3,400 families are not shown on the site because of their objections.

The 25 most frequent surnames are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Privacy and the Internet One of the greatest controversies about genealogical websites is issues related to individual loss of privacy. The large number of individuals and families who have asked not to be listed on Les Fleurs de l'Orient reflect these concerns and raise important issues for genealogists.

Fear of identity theft in the U.S. and other developed countries has spawned legislation that differs from country to country. In most countries, publication of personal data, such as date of birth or any personal data for a living person, is either prohibited or discouraged.

In Australia and the United Kingdom, privacy laws require prior authorization from the individual involved before publication of personal data. The U.S., however, has no state or federal privacy laws, but generally accepted practice prohibits the publication of anything about a living person except first name and family name. Privacy laws in Continental Europe are more restrictive. Publishing anything that could identify a person (including his or her name) is prohibited if the individual objects to the publication.

Based on these criteria, Les Fleurs de l'Orient posted no personal data on living persons born after 1910. Privacy issues cease with death, and data on deceased individuals is published. Any individual's data is deleted from the database upon written request to the webmaster at webmaster@farhi.org.

"I Cherish My Privacy"

Over the many years that Les Fleurs de l'Orient has been operating, I have received many versions of the I-cherish-my-privacy" requests. All have been honored, and the persons names and family have been removed.

Fears of privacy breach cited are numerous, including the following:

Social Security mumbers.

The single greatest privacy issue in the U.S is the widespread overuse and misuse of Social Security numbers. Schools require it; insurance companies use it as a contract number and some states use it as a license number. Lawsuits abound over the misuse of this number. The Social Security number, combined with someone's name and date of birth (both easily obtainable), has allowed individuals to steal thousands of dollars and damage others' credit ratings.

The U.S. Social Security Administration requires two pieces of information in order to secure approval for benefits: the individual's Social Security number and mother's maiden name, exactly as it appears in Social Security's records. When one applies for a Social Security number for a newborn, evidence of the mother's maiden name (e.g., her birth certificate) must be provided. Therefore, someone who steals a Social Security number needs to know the mother's maiden name to redirect benefits. In this case, genealogy sites are a good source of information-if you have discovered that the person is at least 62 years old and, thus, old enough to receive benefits and then want to discover the mother's maiden name. Until recently, Social Security numbers could be found on bank or brokerage statements, which inevitably are discarded, unshredded, in one's daily trash. Anyone going through household refuse easily could steal someone's identity. Fortunately, within the past few years, financial institutions have ceased to print these identifiers on monthly statements.

Credit card fraud.

Fear of credit card fraud truly represents an overblown misconception. Credit card companies use a long list of criteria to determine the identity of a person calling (in an attempt to steal an identity). Usually three questions are asked (such as birth date, address and recent charges) in order to ascertain the identity of a caller. The best way to end the maiden name issue is simply not to register one's mother's real maiden name with anyone. Use her nickname or any other name that you can remember (such as your dog's name). The only case of credit card fraud encountered by someone listed on my website was perpetrated by one of his work associates who had a grudge against him-an "inside job."

Job opportunities.

A few requests to delete a listing were based on the assumption that one could guess someone's age by the birth and death information of his/her deceased relatives, thereby offhand denying a job or an assignment. Usually, however, age can be fairly easily guessed at an interview.

Protection of children.

In one case, parents requested the removal of their children as a jilted high school boy friend was seeking to harass his now-reluctant partner.

Real Reasons for Deleting Requests

After careful investigation of each request for deletion, I have concluded that some were unrelated to concerns about identity theft and real privacy issues. Instead, the implied reasons were to hide origins, religion, mixed marriages or even to hide from family and associates. Anti-Semitism in country of residence often was mentioned. Others complained of "amateurish" genealogy as a hobby and about the publication of names of living people.

In a few cases it was plainly stated:

* "I do not want to be associated with you." Many requests came from public figures whose professional listings followed the Les Fleurs de l'Orient on the Google result page. *

"I do not want my tree published on your site."

Requests came from individuals who found their genealogy posted on Les Fleurs de l'Orient after having been submitted by members of their own families. One request even came from a genealogist who had listed her home address and telephone number on her own site.

Human Factor and Cases of Self-Censorship

In addition to adhering to privacy rules and generally accepted principles of protection of privacy, I also eliminate data that I feel may endanger the persons involved, either in their country of residence or in their work.

Some people live and work in developing countries where knowledge of their religion could jeopardize their status or their work. References to indictments and criminal records also are eliminated, unless officially published by the family. The same is true of family gossip and feuds, underworld connections or assignments with secret services such as the British M16, the CIA or the Mossad, which obviously may be revealed after the death of the individual concerned.

Requests by individuals or relatives always are honored.

The growth of Les Fleurs de l'Orient may be attributed to its visibility and the free sharing of data so everyone may contribute the results of his own research or findings. The publication of this information and sharing it on the Internet is a major part of genealogical research, but we must use good judgment in what we say and publish. Sadly, self-censorship sometimes is needed.